A couple of years ago I wrote a piece called lessons is stupidity: diving the trawl , describing the first time I dived on a trawler’s net. I’ve done this a few times over the years, most recently a couple of days ago. We re-did this because cameras improve and the quality of images improves, so we need to re-shoot. We also wanted to get some slightly different images this time; in particular we wanted to get images as the trawl net was being hauled, when it was just below the surface.

As events transpired the weather conditions were against us. Strong winds prevailed through most of August and much of September. It was not until the last week of September, with equinoxal gales just around the corner, that we finally found a brief window of opportunity. Due to vessel availability and other logistical constraints we had only one day available that week in which everything came together. The weather was marginal but we were now well into autumn with precious few opportunities remaining this year, so we decided to take a chance and go for it.

We began to load the trawl net on to our vessel on a bright but chilly morning. A stiff breeze was whipping whitecaps on the sea beyond the shelter of the harbour, but the latest forecast indicated this should die away during the morning. By the time the net had been hauled aboard and rigged and all our gear on deck it was midday; Lynsey, John and I were hot, dirty and sweaty but pretty satisfied everything was as ready as it could be. The wind had not abated. But we were now committed, so warps were unhitched and we nosed out into the bay. A 60 square mile exclusion area for bottom towed fishing gear (trawls and scallop dredges) has been established within the centre of Lyme Bay to protect the fragile reefs found there (this came about in part due to our earlier work looking at the impacts of bottom-fishing gear). We therefore had a two hour steam to get to a suitable location beyond this closed area in which to set the trawl. That gave us two hours for the wind to die down and the sea state to drop away. If we were lucky the wind would not yet have stirred up the seabed enough to destroy the visibility. The longer the wind continued the more our chances of success diminished.

We reach a shallow bay outside the closed area, about 20 metres depth, shortly after 2.30p.m. The wind was still fresh and we knew it was not looking good for getting workable conditions on the seabed. We decided to have a test dip to check out visibility before deploying the trawl.

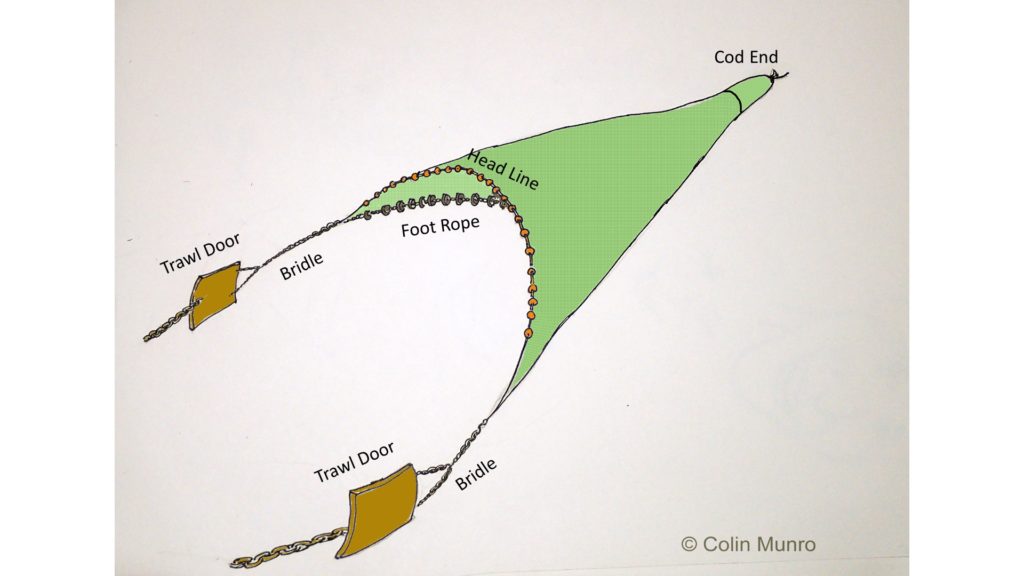

Diagram of the bottm trawl used (not to scale)

I wanted to stay dry in order to do some surface filming of the trawl being deployed, so this task fell to my dive buddy Lynsey. A quick dip was enough to convince her it was no-go. Seabed visibility was no more than one metre. Quite apart from it being impossible to film the trawl operating in such conditions it would also have been too dangerous to be around heavy moving fishing gear. Reluctantly I called the dive off and we reverted to plan B.

Setting up the Gates camera housing in the trawler’s tiny wheelhouse is always a bit of a challenge.

I also wanted to get footage of the trawl as it was being hauled, a little below the surface. This we could do as the near-surface visibility, although far from perfect, was much better than that close to the seabed. However, there were the added logistical problems that the trawl net had to be hauled with the boat steaming forward at a speed of several knots, way too fast to swim or hang on holding a large camera. We had worked a method where I would be dropped off close to the net as it reached the surface, and drift back alongside it, filming as I went. It sounded plausible – I mean what could possibly go wrong? Before this we set up some surface and just below shots at speed, working from a small inflatable.

Poor Lyndsey had the unenviable task of heaving cameras across the tubes to me and hanging on to my legs as I dangled head-down in the water trying desperately to: a) get the vaguest impression of what I was filming through the spray and turbulence, and b) stop my camera from being ripped from my fingers. From the surface I must have presented a highly comical sight, legs waving and coughing and spluttering to the surface every few seconds. From a personal perspective it felt rather like what I imagine being waterboarded by a firehose while suspended upsidedown might feel like. Having had my sinuses thoroughly irrigated at high pressure, it was now time to get into the water, before I had time to ponder the stupidity of my actions and change my mind. At any rate, the sun was racing toward the horizon and light was fading rapidly, so it was either now or call it off and wait ’til next year. In the event the plan worked almost like clockwork; we were even able to repeat the operation so that I could run one haul taking stills and a second taking video footage. Given the relatively poor visibility (~ 4 metres near the surface) I was quite pleased with the results.

The stupid grin you wear when it all works out.

Nothing got broken (apart from a torn shoulder muscle – my stupidity when the trying to work parallel to the waterflow) and everything worked pretty much as it should. October gales have now set in so there will be no more dives on fishing gear this year.

Note: As with my previous blog on this topic, this is NOT in any way designed to be a ‘how to’ guide to diving on trawl nets. I have deliberately ommitted key elements to try to avoid giving this impression. Diving around nets and heavy moving fishing gear obviously involves a significant element of risk if not approached with great care and planning. I have presented this in a fairly light-hearted manner and should be taken as such rather than a technical guide.