I’ve published about Lyme Bay marine biological monitoring on my marine-bio-images blog here and earlier on this blog here, looking at the monitoring of Lyme Bay Closed Area, a Marine protected Area success? Parts 1 and 2 describe the impacts mobile fishing gear, in particular scallop dredging, had been having on the reefs since at least the late 1980s. I describe the impacts of scallop dredging in detail here. I will look soon at the actual monitoring that has taken place since the closed area came in to being in 2008, but before doing so it is probably worth devoting a couple of blogs to describe why Lyme Bay is important and worth protecting; just what makes it special.

What Lyme Bay is not

In seeking to justify protection for the reefs and ‘sell’ the area to the wider public, the concepts of ‘coral gardens’ and ‘charismatic species’ has often been pushed. Such poetic language may well raise the area’s profile and engender support in the short term, but it has lead to some fairly profound misunderstandings – including within NGOs and Government Agencies – about the bay and the reasons the reefs within are important.

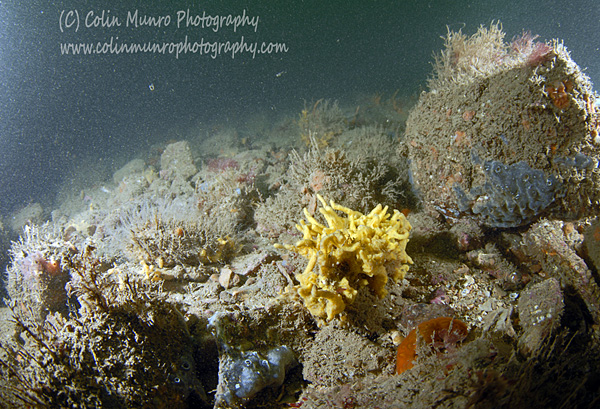

A sediment covered limestone reef in Lyme Bay, Southwest England showing the profusion of sediment tolerant species that grow on such reefs. Image No. MBI001261.

Most of Lyme bay is not visually spectacular, there are few dramatic underwater rock cliffs painted with a riot of colour; nor is it beautiful clear water offering panoramic vistas across the seabed. The reefs in Lyme bay are mostly low lying and the waters tend to be fairly gloomy and turbid. As this is essentially a large, open, sandy bay exposed to the prevailing winds, then significant amounts of suspended sediment (at least near-shore, close to the seabed) are the norm. Whilst winds may ease in summer, it is also prone to strong plankton blooms during May and June, with a second less pronounced bloom in late summer. Thus underwater visibility rarely exceeds 10 metres (30ft) and frequently may be less than 3 metres (10ft). The reefs in the bay, though numerous in the centre and east, are mostly discontinuous, forming a patchwork of low rocky outcrops surrounded by sediment. This means that they tend to be covered by thin veneers of sediment as tide and wave action lifts and sweeps saltating sand across them. The amount of sand will vary, depending on the size of the reef area, how high the reef rises above the surrounding sediment plain, the strength of tidal streams in that part of the bay and how strong the wind has been recently (and thus how big the waves). This makes it a rather challenging environment both the underwater photographer and scientist attempting to record visual data. Low light levels and high levels of suspended sediment producing lots of backscatter from lights making for tricky problems in producing good images.

An area of sediment covered boulder reef, Lyme Bay. The large white sea squirt Phallusia mammillata, and the blue-grey colonial sea squirt Diplosoma spongiforme, both characteristic of Lyme Bay, can be seen in this image. Image No. MBI001264.

The species that make Lyme Bay different and the effects of the Closed Area

The flip side of this is that the communities on these reefs tend to be rather different from those inhabiting areas with perhaps more visually spectacular ‘clean’ reefs further west. Species that tolerate a degree of sand and silt cover do well here. A good example of this is the sponge Adreus fascicularis, a species found almost exclusively on silt-covered horizontal bedrock Considered rare in UK waters, it is relatively common on the reefs of Lyme Bay. Similarly the large solitary sea squirt Phallusia mamillata. A very distinctive species, the largest sea squirt found around British coasts its striking white colour stands out against the dull sediment. More associated with silty, sheltered harbours and estuaries it is uncommon or rare on open coasts along the rest of its UK range, but quite abundant within Lyme Bay. So the factors that make this a difficult environment in which to capture appealing images or gather data on the marine life in quite a significant contribute to Lyme Bay being an interesting and unusual environment. There are other species common here that we simply do not known enough about their ecology to say why they are more abundant in Lyme bay than elsewhere; a good example of this is the colonial sea squirt Diplosoma spongiforme. Though not rare elsewhere, it is abundant in Lyme Bay, forming mats, growing over rocks, seafans and other sponges. Similarly the tassled yellow sponge Iophon hyndmani/Iophonopsis nigricans (the two species are grouped together as very difficult to tell apart underwater) is particularly abundant in Lyme Bay. Indeed the sponge assemblages are frequently very rich and diverse on Lyme Bay reefs; for some reefs such as the boulder reefs (for example Lane’s Ground Reef in the central part of Lyme Bay) they are probably the most obvious characteristic of the reef and may well be the most diverse groups within the reef community there. Unfortunately they are still very poorly described (in part because sponge taxonomy is a difficult subject with field characteristics often not being sufficient for positive identification) and so are certainly under-reported and thus frequently undervalued in terms of the Bay’s conservation value. Yet sponges, being soft tissued and quite often slow-growing species, are amongst the most vulnerable to damage and eradication from areas of reef by mobile fishing gear. Indeed the sharp decline in sponge species occurring on Lane’s Ground Reef between 1995 and 2008 (clearly visible for video footage and still images taken by myself during this time period) was one of the most obvious and disturbing changes in the years before statutory protection from bottom-towed mobile fishing was established for central Lyme Bay.

Boulder reef, Lyme Bay. The amount of suspended sediment in the water can be clearly seen. The yellow tassled sponge Iophon hyndmani or Iophonopsis nigricans can be seen in the centre of the image, however it can be seen that many of the boulders are now (2010) bare of sponges and other attached life. Image No. MBI001267

Has there been a recovery of sponge species since the Closed Area was established in 2008? Our study (running from 2008-2010, when funding from Natural England ended) suggested that sponge recovery was beginning. Three years is too short a time in which to expect marked changes in such communities. It would also be foolish to read much in this data, three annual surveys (i.e. data being collected once a year for three years) represent only three data points. There will obviously be good years and bad years, plus a degree of error in any data collected, so a line drawn from three data points must come with huge caveats. Nevertheless, this slight improvement was noticeable. We are hopeful that we will be able to re-start our monitoring programme, albeit in a slightly reduced form, on a voluntary basis in 2013. It will be exciting to see what effects the Closed Area has had on the reef communities after five years.

More information about Lyme Bay, in particular the impacts of scallop dredging and the protected Closed Area, can be found on my marine biology blog www.marine-bio-images.com/blog, and on the marine-bio-images website where numerous reports on the research we have conducted here can be found.

All text and images in this blog copyright Colin Munro 2012. All images are available to license. Alternatively you can search all my online stock images at my www.colinmunroimages.com site through the search box (top right) or on my main website here.